Dive Brief:

- New Jersey utilities could earn bonuses or incur penalties for beating or failing to meet energy efficiency savings targets, and would be allowed to recover lost revenues related to their efforts, under a Jan. 22 proposal from the state's Board of Public Utilities (BPU).

- New Jersey has been an efficiency laggard in recent years, according to some observers, but the Clean Energy Act of 2018 requires electric utilities to achieve annual energy use reductions of 2% or greater within five years of the new rules being implemented. Gas utilities would need to achieve annual energy use reductions of 0.75%.

- The cost recovery proposal issued Wednesday follows a straw proposal in December that outlined how utility efficiency programs will be administered and recommended implementation of new energy-saving pilots.

Dive Insight:

Energy efficiency will be a vital tool in the Garden State's bid to reach 100% clean energy by 2050, but that will require making significant strides from today's reality, according to experts.

"New Jersey has had one of the most-costly and least-effective energy efficiency programs in the country, so there really needs to be changes," Sierra Club New Jersey Chapter Senior Director Jeff Tittel told Utility Dive.

The energy efficiency straw proposal and cost recovery plan would help implement a significant overhaul of New Jersey’s energy system that Gov. Phil Murphy (D) signed in May. The measure boosted efficiency targets and set a 50% renewable goal by 2030, paving the way for additional solar, wind and storage resources.

But until now, how utilities would approach efficiency improvements — and how they would pay for it under the 2018 law — had not been addressed. Even now, Tittel said the process remains in the early stages with public input still being considered.

"We know that to meet the state’s ambitious [energy efficiency] goals from the 2018 Clean Energy Act, the state needs to ensure utilities have adequate cost recovery and incentives aligned with delivering energy efficiency savings," Rachel Gold, utilities manager for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), said in an email.

"This first draft proposal looks like it moves in that direction, and provides a good opportunity for stakeholders to provide input," Gold said. "But the details matter, and it will be important for stakeholders to weigh in on the details of the proposal mechanism."

ACEEE ranked New Jersey 17th last year in its annual comparison of states; however, the utility sector overall scored just 6.5 out of 20 points. The analysis noted that the state's 2018 energy savings remained below the national average, but that the BPU was in the process of developing utility-specific targets and metrics.

PSEG, the largest utility in New Jersey, declined to comment on the cost recovery proposal.

"They will press for as much recovery as possible. That's what always happens, and hopefully it will all work out," Tittel said.

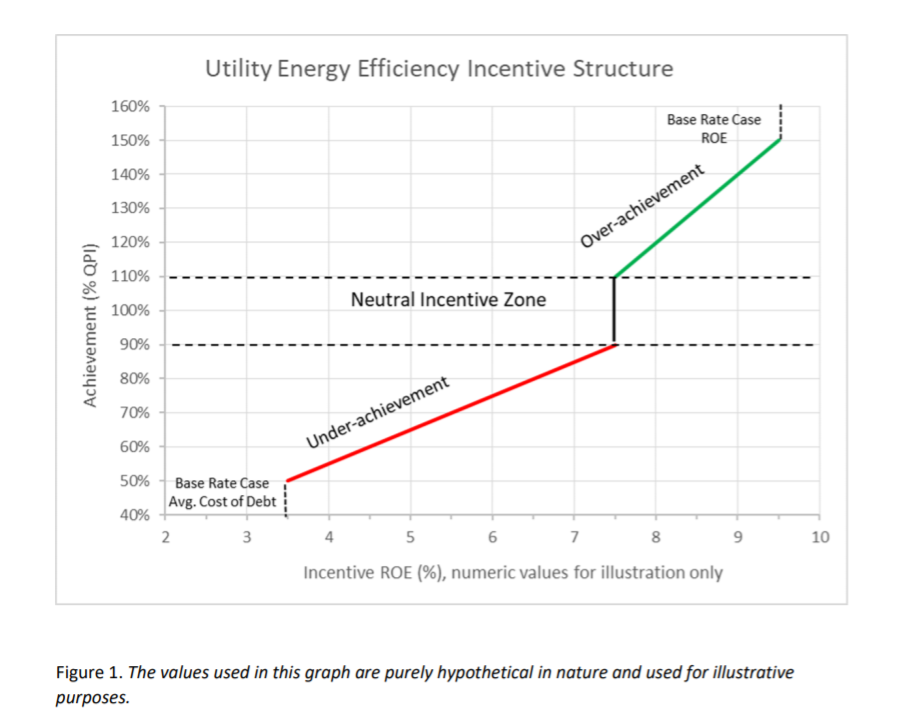

Under the cost recovery proposal, utilities would face a performance penalty for achieving between 50% and 90% of a quantitative performance indicator (QPI) of savings that could include energy savings, demand savings, savings over the course of a program's lifetime, and other metrics.

"There will be a neutral area, or buffer, within which there will be no incentive awarded or penalty assessed, ranging from 90% to 110% of the QPI achievement," the proposal says. Utilities would see a performance incentive award for achieving between 110% and 150% of the QPI achievement.

"The performance incentive and the performance penalty will both take the form of a return on equity adjustment applied to energy efficiency transition program investment, similar to the structure in place in Illinois," the proposal explains.

Utilities will also be able to recover lost revenues, but the proposal specifies they must be able to demonstrate revenue declines "were attributable to the utility-run energy efficiency and peak demand reduction program(s)."

Measuring and verifying efficiency savings will be a "key piece" of making the program successful, said Tittel. New Jersey is already seeing some energy use declines, between 0.5% and 1% annually as consumers adopt more energy-efficiency technologies, Tittel said.

"We want to make sure the reductions are real reductions, and not based on market trends or weather," Tittel said. "We want to make sure it's not just on paper."

Despite current declines in energy use, Tittel said efficiency would be vital for the state because of the expected growth in electric vehicle adoption and the electrification of the heating sector.

"Electricity use is going to be rising, so energy efficiency becomes more important so we don't have to build excess [generating] capacity," he said.